edited from http://www.225batonrouge.com and https://groups.google.com:

Harry Oster, a young English professor from LSU, was one of those people who saw past the racial and social walls separating polite society and this backwoods culture and set on a career of preserving it.

His recording in the late ’50s and early ’60s at Angola Penitentiary and his 1969 book Living Country Blues are both crucial pillars in the history of the blues. His two collections Prison Worksongs and Angola Prisoner’s Blues (Arhoolie 448 and 419, respectively) are landmark documents celebrating the human spirit triumphant in the worst of conditions.

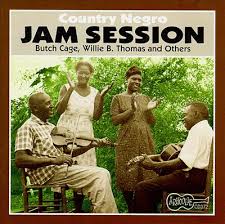

The music he captured on tape—all being continually released by San Francisco folk label Arhoolie—is hypnotic stuff. It is triumphant music that doesn’t shy away from the conditions in which it was created but rises above it. But Oster’s arena was not just within prison walls. One of his finest collections, the notoriously titled Country Negro Jam Sessions is a veritable treasure chest of intricate country blues, starting out the gate with the infectious “.44 Blues” by fiddler Butch Cage and guitarist Willie B. Thomas. Oster recorded this duo extensively in Zachary in the ’60s preserving the dying art of country string band music, which has the rootsy funk of old jug bands, the swing of Cajun fiddle music and the knuckle punch of the blues.

Among the 3800 convicts in the desolate flatland of the prison farm at Angola, Louisiana, there were a surprising number of talented performers. Several of them were recorded and interviewed by folklorist Dr. Harry Oster between 1952 and 1960, and some of this material was originally issued on his Folklyric label. These are raw, powerful, largely improvised personal blues stories, as well as traditional songs. This CD features many previously unreleased items including the haunting monologue from Roosevelt Charles which ends the record, as well as unreleased tracks by women singers Odea Mathews, Clara Young and Thelma Mae Joseph.

Angola prison was just about 50 miles away.BN: Were prisoners willing to sing for you?

cooperation with authorities, maybe it would do them good one way or

another.BN: As you said, in 1959 you started up your own recording label, Folk-Lyric.

How did you do printing records, distribution, promotion, and things like

that?

HO: Eventually I heard that RCA had a customs pressing plant in Indianapolis

and I started sending stuff to them and getting stuff professionally printed.

I would send out review copies to major newspapers like New York Times,

Down Beat Magazine, Saturday Review, and some newspapers. They gave them

good attention and I got in touch with some distributors. My label was

essentially one-man operation. I would find performers, record them, edit

the tapes, take photographs, write liner notes, etc. I would generally

press about 300 copies. I borrowed $5,000 from a bank to subsidize the

operation. I also did some assignments for other companies, and that

helped finance it also. I did one record for Elektra which was eventually

sold to Folkways. I did some for Prestige Bluesville and Prestige

International.

BN: What was your major motivation for getting into that kind of business?

HO: I just enjoyed doing records. It was exciting and fascinating and engaging.I wasn’t trying to get rich doing that, actually I tried to avoid losing money.

Leave a comment