On a muggy Sunday afternoon in June of 1959, John Cohen wandered the winding mountain roads of eastern Kentucky searching for old-time musicians. Neon, Bulan, Vicco, Viper, Daisy, Defiance — tiny coal and timber towns with sonorous names popped up around each bend before giving way to the Cumberland Mountains. Cohen had come to Kentucky from New York City to find songs about “hard times” that would fill out the repertoire of his old-time music group, the New Lost City Ramblers. “In order to experience an economic depression firsthand, I visited eastern Kentucky and made photos and field recordings for six weeks in 1959,” he recalled.1 “The United States was quite prosperous at that point, but east Kentucky wasn’t and I had heard about that. . . . And I said, ‘Maybe I can find some music about the depression, experience the depression, and understand it more and maybe photograph it, maybe record music.'”2

|

Map used by Cohen to navigate Kentucky, 1959.

|

John Cohen, Two girls walking, Vicco, KY, 1959.

|

Later in the day, Cohen began to wonder whether his trip was in vain. He had exhausted every name on his search list of banjo players and he had no desire to return to the hot boarding house room along the railroad tracks of Hazard. Earlier, he had visited an eighty-five-year-old fiddler, Wade Woods, but Woods could barely play anymore. On a whim, Cohen took the first dirt road that led off the main highway to see what or who might turn up. Turning off the hardtop, he crossed over a little bridge and stream and entered a lumber-mill village called Daisy. He approached a couple of small houses and, at the first one, asked some children standing out front, “Any banjo players around here?”

“Over there in that house,” they replied.

Cohen pulled up and recognized a young man named Odabe Halcomb he had recorded the night before at a nearby roadhouse.

“What are you doing here?” Halcomb asked, surprised to see this outsider on his doorstep.

“Well, I’m looking for music,” Cohen said.

Halcomb turned to his adopted aunt, and Cohen asked her to play a banjo tune. Mary Jane Halcomb played a couple of songs including, “Charles Guiteau,” about assassin of President James A. Garfield. Suddenly she announced, “Here comes Rossie!”

|

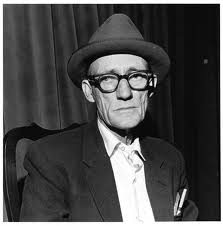

| John Cohen, Roscoe Holcomb, Daisy, KY, 1959. |

A wiry and weathered man, aged forty-seven, Roscoe Halcomb walked toward the house.3 A manual laborer and former miner, Halcomb lived at the very end of the hollow in Daisy. After some cursory introductions, Halcomb played a song for Cohen called “Across the Rocky Mountain.” “My hair stood up on end,” Cohen later remembered. “I couldn’t tell whether I was hearing something ancient, like a Gregorian Chant, or something very contemporary and avant-garde.” The combination of pulse-like rhythm, coupled with the high, tight singing, and the insistent droning notes of the guitar had its effect. “It was the most moving, touching, dynamic, powerful song I’d ever experienced . . . not the song itself but they way he sang it was just astounding. And I said, ‘Can I come back and hear you some more?'”4

On a muggy Sunday afternoon in June of 1959, John Cohen wandered the winding mountain roads of eastern Kentucky searching for old-time musicians. Neon, Bulan, Vicco, Viper, Daisy, Defiance — tiny coal and timber towns with sonorous names popped up around each bend before giving way to the Cumberland Mountains. Cohen had come to Kentucky from New York City to find songs about “hard times” that would fill out the repertoire of his old-time music group, the New Lost City Ramblers. “In order to experience an economic depression firsthand, I visited eastern Kentucky and made photos and field recordings for six weeks in 1959,” he recalled.1 “The United States was quite prosperous at that point, but east Kentucky wasn’t and I had heard about that. . . . And I said, ‘Maybe I can find some music about the depression, experience the depression, and understand it more and maybe photograph it, maybe record music.'”2

|

Map used by Cohen to navigate Kentucky, 1959.

|

John Cohen, Two girls walking, Vicco, KY, 1959.

|

Later in the day, Cohen began to wonder whether his trip was in vain. He had exhausted every name on his search list of banjo players and he had no desire to return to the hot boarding house room along the railroad tracks of Hazard. Earlier, he had visited an eighty-five-year-old fiddler, Wade Woods, but Woods could barely play anymore. On a whim, Cohen took the first dirt road that led off the main highway to see what or who might turn up. Turning off the hardtop, he crossed over a little bridge and stream and entered a lumber-mill village called Daisy. He approached a couple of small houses and, at the first one, asked some children standing out front, “Any banjo players around here?”

“Over there in that house,” they replied.

Cohen pulled up and recognized a young man named Odabe Halcomb he had recorded the night before at a nearby roadhouse.

“What are you doing here?” Halcomb asked, surprised to see this outsider on his doorstep.

“Well, I’m looking for music,” Cohen said.

Halcomb turned to his adopted aunt, and Cohen asked her to play a banjo tune. Mary Jane Halcomb played a couple of songs including, “Charles Guiteau,” about assassin of President James A. Garfield. Suddenly she announced, “Here comes Rossie!”

|

| John Cohen, Roscoe Holcomb, Daisy, KY, 1959. |

A wiry and weathered man, aged forty-seven, Roscoe Halcomb walked toward the house.3 A manual laborer and former miner, Halcomb lived at the very end of the hollow in Daisy. After some cursory introductions, Halcomb played a song for Cohen called “Across the Rocky Mountain.” “My hair stood up on end,” Cohen later remembered. “I couldn’t tell whether I was hearing something ancient, like a Gregorian Chant, or something very contemporary and avant-garde.” The combination of pulse-like rhythm, coupled with the high, tight singing, and the insistent droning notes of the guitar had its effect. “It was the most moving, touching, dynamic, powerful song I’d ever experienced . . . not the song itself but they way he sang it was just astounding. And I said, ‘Can I come back and hear you some more?'”4

excerpt from “John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky: Documentary Expression and the Image of Roscoe Holcomb During the Folk Revival,” by Scott L. Matthews:

On a muggy Sunday afternoon in June of 1959, John Cohen wandered the winding mountain roads of eastern Kentucky searching for old-time musicians. Neon, Bulan, Vicco, Viper, Daisy, Defiance — tiny coal and timber towns with sonorous names popped up around each bend before giving way to the Cumberland Mountains. Cohen had come to Kentucky from New York City to find songs about “hard times” that would fill out the repertoire of his old-time music group, the New Lost City Ramblers.

“In order to experience an economic depression firsthand, I visited eastern Kentucky and made photos and field recordings for six weeks in 1959,” he recalled. “The United States was quite prosperous at that point, but east Kentucky wasn’t and I had heard about that. . . . And I said, ‘Maybe I can find some music about the depression, experience the depression, and understand it more and maybe photograph it, maybe record music.'”

Later in the day, Cohen began to wonder whether his trip was in vain. He had exhausted every name on his search list of banjo players and he had no desire to return to the hot boarding house room along the railroad tracks of Hazard. Earlier, he had visited an eighty-five-year-old fiddler, Wade Woods, but Woods could barely play anymore. On a whim, Cohen took the first dirt road that led off the main highway to see what or who might turn up. Turning off the hardtop, he crossed over a little bridge and stream and entered a lumber-mill village called Daisy. He approached a couple of small houses and, at the first one, asked some children standing out front, “Any banjo players around here?”

“Over there in that house,” they replied.

Cohen pulled up and recognized a young man named Odabe Halcomb he had recorded the night before at a nearby roadhouse.

“What are you doing here?” Halcomb asked, surprised to see this outsider on his doorstep.

“Well, I’m looking for music,” Cohen said.

Halcomb turned to his adopted aunt, and Cohen asked her to play a banjo tune. Mary Jane Halcomb played a couple of songs including, “Charles Guiteau,” about assassin of President James A. Garfield. Suddenly she announced, “Here comes Rossie!”

A wiry and weathered man, aged forty-seven, Roscoe Halcomb walked toward the house.3 A manual laborer and former miner, Halcomb lived at the very end of the hollow in Daisy. After some cursory introductions, Halcomb played a song for Cohen called “Across the Rocky Mountain.”

“My hair stood up on end,” Cohen later remembered. “I couldn’t tell whether I was hearing something ancient, like a Gregorian Chant, or something very contemporary and avant-garde.” The combination of pulse-like rhythm, coupled with the high, tight singing, and the insistent droning notes of the guitar had its effect. “It was the most moving, touching, dynamic, powerful song I’d ever experienced . . . not the song itself but they way he sang it was just astounding. And I said, ‘Can I come back and hear you some more?'”